Strengthening Drone Detection with Bio-Inspired Algorithms and Knowledge Distillation

Feb. 29, 2024

In the event no signal is received after two minutes, a timed relay will place the robot plane, or ‘DRONE’, as it will be called hereafter, in a turn.

— Radio Control of Aircraft

From behind the headboard slipped a tiny hunter-seeker no more than five centimeters long. Paul recognized it at once — a common assassination weapon….It was a ravening sliver of metal guided by some near-by hand and eye. It could burrow into moving flesh and chew its way up nerve channels to the nearest vital organ.

— Dune

Let me be the firstI’m not so innocentLet me be the oneThe one that you choose from aboveAfter allI’m partly to blameSo drone bomb me— Anhoni

Introduction

Drones hum and hover above every continent on Earth, omnipresent and inconspicuous. A wide and diverse swath of society—militaries and militias, farmers, black market peddlers and private enterprises, beach lifeguards, and consumers of all ages—avails itself of the airborne drone within the largely unregulated “Wild West” of the lower skies. The implications are manifold and well documented.

Computer vision models augment considerably the sensor-specific capabilities for drone detection such as acoustic, electro-optical, and radio frequency (RF) sensors. Some of the current pain points of innovation in the domain of real-time drone detection, and those which computer vision models can especially mitigate, consist of the following: detecting small drones from a great distance and against complex backgrounds, such as dense urban areas; detecting drones that exploit the vulnerabilities in current detection systems by stealthily hiding amongst large obstacles such as trees, mountains, and high-rise buildings; and improving the speed and accuracy of detecting drones in real-time video feeds, such as those from visible and infrared spectrum cameras.

In this proposal, we first present a comprehensive review of current computational techniques for drone detection, including biologically-inspired vision (BIV) algorithms and deep Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). Secondly, to mitigate the pain points around innovation in this space, we propose experimenting with a combination of BIV algorithms for more advanced signal pre-processing and feature extraction, scarce data augmentation techniques on existing publicly available datasets, and CNN architectures that are uniquely well-suited for detecting drones in real-time video feeds. Through informed experimentation, we aspire to present a novel computer vision model that will mitigate the aforementioned pain points as well as lower the overall cost barrier for real-time drone detection. Finally, we present the best dataset candidates for model experimentation from amongst those that are publicly available.

Review of Computational Techniques

In this section, we discuss innovative computational techniques which have arisen from the fields of signal processing and artificial intelligence, in particular biologically-inspired vision (BIV) algorithms and deep Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). These computational techniques complement and augment device-specific sensor modalities which ultimately enhance their capacity for more accurate drone detection.

Biologically-Inspired Vision Algorithms

Biologically-inspired algorithms draw inspiration from natural processes and biological systems, applying principles such as replicating the highly efficient visual processing capabilities found in biological organisms, e.g., birds, insects, and primates, to enhance drone detection and localization performance. Some of the biological neural mechanisms that have been applied successfully to artificial visual systems are lateral inhibition, visual attention, contrast sensitivity, and motion processing.

Entomological Physiology

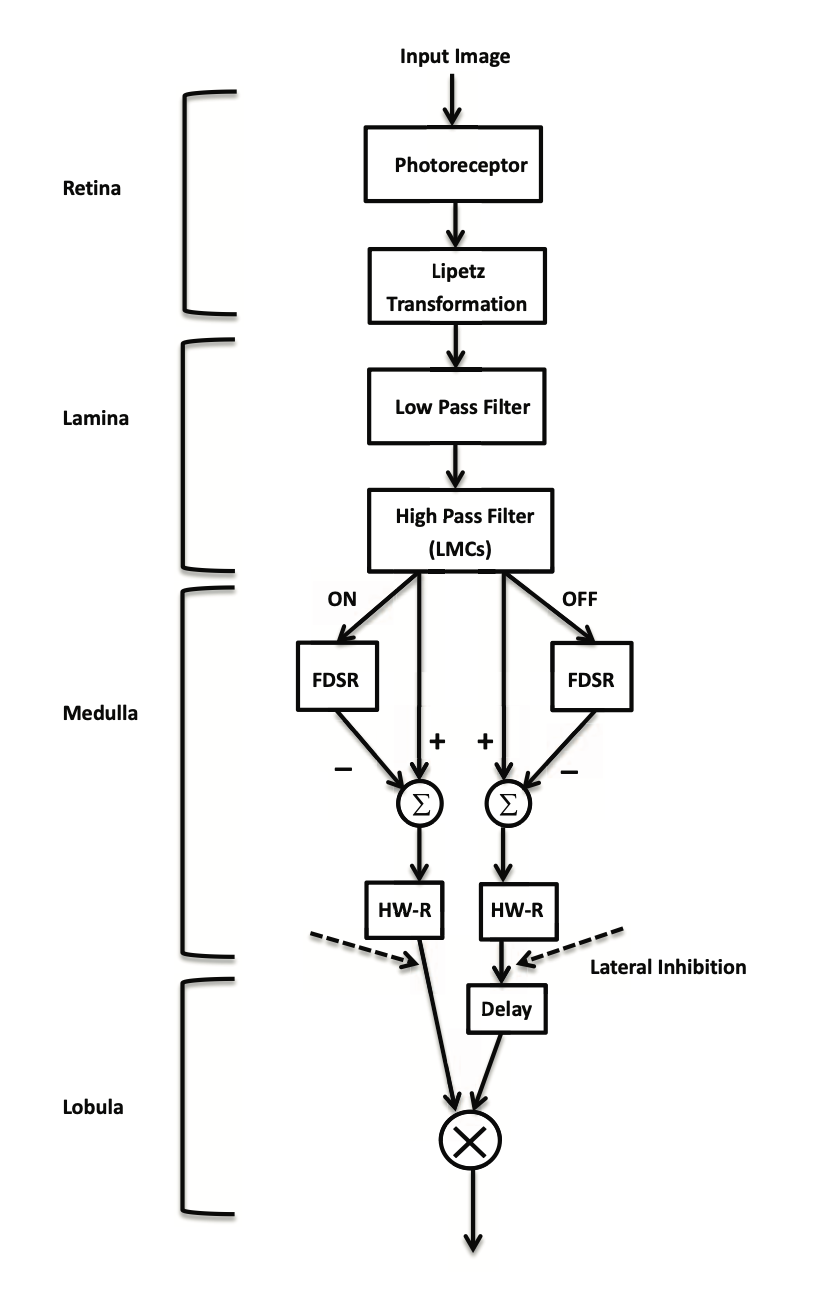

The roots of current advances in computational applications based on entomological visual systems emerged from studies put forth by O’Carroll (1993), Shoemaker (2005), and Wiederman (2007). Wiederman (2008) originally proposed a BIV model based on flies’ (Calliphora) specialized neurons responsible for small moving targets known as small target motion detectors (STMDs). The artificially-replicated model in computer vision is known as the elementary small target motion detector (ESTMD). More recent studies (Wang, 2016; Wiederman, 2022) have proposed extending the ESTMD model to dragonflies (Hemicordulia tau) based on the work of O’Carroll (1993).

Lateral inhibition, as replicated in the original ESTMD model, is typically achieved by inhibiting background motion to enhance small target motion more effectively; however, too much lateral inhibition, particularly in the periphery, can lead to unstable detection performance, as observed in the original model. Building upon the work of Wiederman (2008), Wang (2016) proposes a modified ESTMD model that incorporates a more biologically-plausible lateral inhibition mechanism with motion velocity and direction to improve discriminating the motion of the target from the motion of the background, a feature which has a physiological basis in the dragonfly’s higher order neurons. A more detailed discussion around lateral inhibition in retinal neurons is given in Srinivasan (1982).

Melville-Smith (2022) proposes a novel nonlinear lateral inhibition scheme, leveraging optic-flow signals for dynamic signal conditioning, which significantly improves target detection performance from moving platforms and suppresses false positives. The proposed approach achieves an improvement in detection accuracy of 25% over linear inhibition schemes and 2.33 times the detection performance over conventional BIV models, such as ESTMD, without inhibition.

Wiederman (2022) builds on their earlier work (Wiederman, 2008) to modify the ESTMD model that leverages the visual processing abilities of dragonflies, in particular their ability to detect small moving targets (i.e., their prey) against complex backgrounds in low-resolution (i.e., “blurred”) settings. These abilities are ideally suited in environments where computational resources are limited, such as with real-time small drone detection in the field. The results indicate that combining outputs from light and dark contrast model variants, designed to mimic more physiologically realistic values, improves recall, especially at lower resolutions. Performance is influenced by the apparent size and speed of the drone in the image plane, with the model struggling at extreme speeds or smaller apparent sizes. Reduction in spatial resolution decreased detection performance but reduced computational demands.

Recent studies have sought to extend conventional BIV models from flies to pre-processing techniques for thermal infrared video frames containing small drones against low contrast backgrounds. Uzair (2019) incorporates adaptive temporal filtering and spatio-temporal adaptive filtering, inspired by the photoreceptor cells and large monopolar cells of small flying insects. Their method significantly improves detection performance by enhancing target contrast against cluttered backgrounds and suppressing noise. Experiments demonstrate that these pre-processing techniques enhance the effectiveness of the four standard infrared detection algorithms: the baseline multiscale morphological top-hat filtering, the saliency detection method using local regression kernels, the multiscale local contrast measure, and the infrared path-image model. Detection rates of the best performing model increased by 100%.

Uzair (2021) addresses the limitations of detecting small, thermally minimal targets within infrared imagery through a four-stage BIV-based target detector, utilizing inspiration gleaned from flying insects’ visual system as proposed in Uzair (2019). Their model overcomes such challenges as sensor noise, minimal target contrast, and cluttered backgrounds with an improvement of over 25 dB in signal-to-clutter ratio and a 43% higher detection rate than the existing best methods.

Primate Physiology

Broadly speaking, BIV algorithms based on primate physiology fall into the following categories: cognitive; information theoretic; graphical; spectral analysis; pattern classification; Bayesian; and decision theoretic (Borji & Itti, 2013). For the purpose of this paper, we focus on those cognitive, graphical, and spectral models which simulate early visual processing stages in primates, particularly in the context of attention mechanisms and saliency detection.

Itti, Koch, and Niebur (1998) explore the early visual system of primates which excels at interpreting complex scenes and focusing attention in real time through the bottom-up use of saliency maps. The authors implement a dynamic neural network architecture that mimics this visual system, in particular a saliency-driven focal visual attention for target detection which utilizes center-surround mechanisms to extract conspicuous features across different scales without requiring top-down guidance; a biologically-plausible winner-take-all mechanism which allows the model to sequentially attend to different locations based on their saliency; and adaptation to scene context in which the model changes its focus in response to the evolving content of the scene. The results of this cognitive model indicate that its attentional trajectories perform similarly to human eye fixations and is therefore a computationally efficient means for real-time target detection.

Given the human visual system’s strong ability to detect saliency, Hou and Zhang (2007) propose a spectral residual approach which mimics the way the human retina and early visual cortex prioritize regions of interest in the visual field, extracting those features which stand out. By analyzing the spectral residual in an image’s log spectrum, their approach taps into a fundamental aspect of human visual perception. While the spectral residual method achieves the same hit rate (HR) of 0.5076 as Itti, Koch, and Niebur (1998), it does demonstrate a significant improvement in reducing the false alarm rate (FAR) to 0.1688 from Itti, Koch, and Niebur’s (1998) FAR of 0.2931. Additionally, the spectral residual method is substantially more efficient, requiring only 4.014 seconds for computation, as opposed to 61.621 seconds needed by the Itti, Koch, and Niebur (1998) model.

Harel, Koch, and Perona (2007) improve upon Itti, Koch, and Niebur (1998) with a Graph-Based Visual Saliency (GBVS) model for bottom-up visual saliency. To improve conspicuity, GBVS improvements include forming and normalizing activation maps on feature channels utilizing a graph-based method to better simulate human visual attention. Their method achieves 98% of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) area of a human-based control compared to the Itti, Koch, and Niebur (1998) model’s 84%.

Hérault (2010) developed a model of the neural connections within the human retina highlighting the importance of spatio-temporal filtering for pre-processing images. This model has influenced the creation of the human retina model described in the Methodology section which uses spectral whitening to replicate how the human visual system equalizes different frequency components to focus on important features. Hérault (2010) also delves into circuits for processing motion and color in the retina as well as studying the adaptive nonlinear characteristics of photoreceptors. These aspects demonstrate how the retina functions as a network system that cleans and prepares information for further computational analysis.

McIntosh and Maheswaranathan (2015) employ CNNs to predict spiking activity in retinal ganglion cells in response to stimuli such as spatio-temporal binary noise, aiming to enhance the understanding of how the retina responds. Due to their heightened sensitivity towards noisy backgrounds, attention mechanisms inspired by vision algorithms with both bottom-up and top-down approaches tend to outperform more basic models (Borji & Itti, 2013). Bottom-up models are computationally faster as they react to stimuli in a visual scene and are more responsive to visual disturbances. On the other hand, top-down approaches, driven more by specific task requirements than sensory stimuli, tend to be slower and less responsive to interference. Therefore, when it comes to tasks like drone detection in challenging settings that involve spotting small targets, combining a bottom-up approach (using passive retinal-like inputs) with a top-down approach (utilizing an active cognitive-like guide to maintain focus) could offer promising opportunities for further exploration. This integrated method is considered as part of our methodology in the Methodology section.

Yang (2023) presents a motion-guided visual detection system inspired by the human visual system and its attention response triggered by motion called the “motion-guided video tiny object detection method” (MG-VTOD). Employing a YOLOv5 framework as its foundation, MG-VTOD captures motion cues from moving targets such as drones. A unique motion strength algorithm generates a grayscale map that highlights moving objects against backgrounds when overlaid on video frames. During trials conducted in environments with occlusions such as clouds, buildings, forests, and mountains, the MG-VTOD model has shown better performance compared to other methods such as the vanilla small variant YOLOv5-s (v8 is detailed in the YOLOv8 section) and FCOS (discussed in the FCOS section).

Deep Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

Deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are well suited for drone detection given their multiple, hierarchical layers which are capable of identifying and localizing objects against complex backgrounds. Through the process of convolution, spatial relationships in images and videos are preserved. There are two main types of object detection algorithms that are implemented within deep CNNs: two-stage and one-stage. Two-stage object detectors, such as Region-based CNNs (R-CNNs), generate region proposals which are areas that are likely to contain the target object; these detectors then classify the regions into object categories and refine the bounding boxes (i.e., the location and size of the objects). While two-stage detectors are more accurate, they are slower due to the additional proposal generation.

In contrast, one-stage object detectors such as YOLO (“You Only Look Once”) and Fully Convolutional Networks (FCNs) bypass the proposal generation step and directly predict object categories and their corresponding anchor boxes in a single pass. The architecture of FCNs, neural networks which are fully convolutional, i.e., without any fully connected layers in the final output, has been adapted as single-stage object detectors to make predictions on a per-pixel basis across an entire image. One-stage detectors have traditionally sacrificed some accuracy for greater real-time speed, although that gap is closing in the wake of recent innovations. Advanced signal pre-processing and feature extraction techniques are also discussed in this section.

Advanced Signal Pre-Processing and Feature Extraction Techniques

Advanced signal pre-processing and feature extraction techniques, such as noise reduction, contrast adjustment, attention mechanisms, and normalization, improve a CNN’s ability to learn from more refined sensor data as measured by greater detection accuracy and reduced false positives. Ding (2023) proposes an acoustic denoising pre-processing module as part of a hybrid Convolutional-LSTM (long short-term memory) neural network typically reserved for such tasks as sound separation and speech enhancement. Their model, called DroneFinderNet, improves detection sensitivity by separating drone sounds from background noise.

To mitigate challenging situations such as environments with high visual noise levels and the presence of visually similar objects, Han (2024) proposes RANGO to strengthen feature extraction methods of the object-detecting YOLOv5 model. RANGO adds a Preconditioning Operation (PREP) to improve target-background contrast; a parallel convolution kernel in the Cross-Stage and Cross-Feature Fusion of the CSPDarknet53 module; and a Convolutional Block Attention Module and Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling for more focused feature attention. Compared to a vanilla YOLOv5 implementation, YOLOv5 with RANGO reduced the drone missed detection rate by 4.6% and increased the average recognition accuracy by 2.2%.

Fully Convolutional One-Stage Object Detector (FCOS)

The novel Fully Convolutional One-Stage Object Detector (FCOS) is given by Tian et al. (2022). It is a fully convolutional neural network; one stage; and anchor free, i.e., without the need for pre-defined anchor boxes as reference points to predict the presence of objects which is far more computationally intensive. FCOS predicts the presence and boundaries of objects at the level of the pixel, without relying on predefined anchor box shapes and sizes. This adjustment simplifies the model by removing the need for calculating Intersection over Union (IoU) scores and additional hyperparameters for each anchor box. FCOS achieves similar recall rates to anchor-based methods, such as YOLO, but with improved performance and faster inference speeds. In their research, Nayak (2022) suggests a data augmentation technique to optimize FCOS for drone detection.

YOLOv8

YOLOv8 (Ultralytics, 2023) is a computer vision object detection model first developed by Redmon (2016). The model detects objects in images or videos and pinpoints their locations using bounding boxes. YOLOv8 operates on a CNN framework that processes the image or video frame in such a way that it predicts object classes and locations in a single pass, hence the name “You Only Look Once”. This method of processing data in a single pass is much quicker than classical convolutional techniques that analyze parts of images separately using sliding windows.

Kim (2023) proposes an updated version of the YOLOv8 architecture by integrating Multi Scale Image Fusion (MSIF) and a P2 Layer to enhance the recognition and differentiation of objects, such as distinguishing between birds and drones, especially when they are at a great distance away from the sensors. Their model achieves a speed of 45.7 fps with the P2 layer and MSIF using a 640p image size dropping to 17.6 fps with a 1280p image size.

Bennour (2023) presents experiments with YOLOv8 and YOLOv7 variants to optimize for real-time detection speed, accuracy, and computational efficiency. The YOLOv8n model had the best performance in terms of both frames per second and Average Precision (AP50): 107.53 fps with an AP50 score of 99.5%. While the YOLOv7 also demonstrated similar accuracy levels, the inference speed of the YOLOv8n model was much faster.

Reis (2023) enhances feature extraction and object detection by combining a Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) with a Path Aggregation Network (PAN). In addition to these modifications to the YOLOv8 framework, they introduce auto-labeling tools to streamline the process of annotating model training data. Furthermore, their model incorporates more advanced post-processing techniques such as Soft NMS (non-maximum suppression). Their modified YOLOv8 model maintained inference speed while increasing the accuracy.

Methodology

To mitigate the main pain points discussed in the Introduction, we propose a series of at least three experiments. For both the network backbone and the baseline, we propose utilizing variations of YOLOv8. For more advanced pre-processing and feature extraction techniques, we will implement variations of the human retina model from OpenCV (OpenCV, 2023). And finally, given that the experimental models are likely to be quite large, we propose to explore Knowledge Distillation as a means to transfer the learning to a smaller model that will still preserve detection accuracy. Combining these three approaches is an important contribution to the field of drone detection.

Candidate Datasets

In this section, we present candidate computer vision datasets in tabular form drawn from various modalities and sensor technologies for the purpose of drone detection.

| Citation | Data Type | Volume | Resolution | Features | Conditions | Format |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acoustic | ||||||

| Audio Based Drone Detection and Identification Dataset | ||||||

| Al-Emadi (2019) | Audio Clips | Over 1300 | CD quality | Drone sounds, augmented clips | Indoor environment | MPEG-4 audio format |

| Electro-Optical | ||||||

| Amateur Unmanned Air Vehicle Detection Dataset | ||||||

| Aksoy (2019) | Images | Over 4000 | - | DJI Phantom series drones, negative objects | Sourced from YouTube and Google | JPEG, text files |

| “An insect-inspired detection algorithm for aerial drone detection” Dataset | ||||||

| James (2018) | Videos | 5 | 1080p and 720p | Phantom 4 Pro drone, various conditions | Urban, parklands, suburbs | - |

| Drone-vs-Bird Detection Challenge Dataset | ||||||

| Coluccia (2017) | Videos | 5 videos | MPEG4 | Annotations for drone frames | Various backgrounds & illumination | Separate annotation files |

| Drone Model Identification by CNN from Video Stream Dataset | ||||||

| Wisniewski (2021) | Images | - | - | 3 DJI models, randomized backgrounds | Synthetic, Blender-generated | PNG |

| Multi-Target Detection and Tracking from a Single Camera in UAVs Dataset | ||||||

| Li (2022) | Videos | 50 sequences, 70250 frames | 1920x1080 / 1280x1060 | Multiple target UAVs, manual annotations | Captured with GoPro 3 | VATIC annotations |

| Segmented Dataset Based on YOLOv7 for Drone vs. Bird Identification | ||||||

| Srivastav (2023) | Images | 20925 | 640x640 | Birds and drones in motion, augmentation | Various conditions | JPEG, plaintext files |

| SUAV-DATA Dataset | ||||||

| Zhao (2023) | Images | 10000 | - | Small, medium, large drones | All-weather, diverse angles | - |

| UAV Traffic Dataset for Learning Based UAV Detection | ||||||

| Enfv (2022) | Packet Headers | - | - | Six commercial drones | - | .csv files |

| USC Drone Dataset | ||||||

| Wang (2019) | Videos | 30 clips | 1920x1080 | Model-based augmentation, diverse scenarios | Varying backgrounds, weather | - |

| Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Dataset | ||||||

| Makrigiorgis (2022) | Images | 1535 | - | Multiple angles and lighting conditions | - | COCO, YOLO, VOC formats |

| LIDAR | ||||||

| Drone detection in LIDAR depth maps Dataset | ||||||

| Carrio (2018) | Depth Maps | 6000 | - | Various drone models, environments | Indoor and outdoor | - |

| Radio Frequency | ||||||

| Cardinal RF Dataset | ||||||

| Medaiyese (2022) | RF Signals | - | - | UAV controllers, UAVs, Bluetooth, Wi-Fi | Visual and beyond-line-of-sight | MATLAB format |

| Drone Remote Controller RF Signal Dataset | ||||||

| Ezuma (2020) | RF Signals | ~1000 per RC | - | 17 drone RCs, 2.4 GHz band | - | MATLAB format |

| DroneRF Dataset | ||||||

| Al-Sad (2019) | RF Signals | 227 segments | - | Various drone modes, background activities | - | - |

| RF-based Dataset of Drones | ||||||

| Sevic (2020) | RF Signals | - | - | Communication signals between drones and control stations, frequency hopping techniques | - | - |

| VTI_DroneSET_FFT Dataset | ||||||

| Sazdic-Jotic (2021) | RF Signals | - | - | DJI drones, operational mode changes | - | - |

| Multi-Modal: Infrared and Electro-Optical | ||||||

| Anti-UAV Dataset | ||||||

| Zhao (2023) | Videos | - | Full HD | RGB and IR, dense annotations | Real-world dynamic scenarios | - |

| VisioDECT Dataset | ||||||

| Ajakwe (2022) | Images | 20924 | - | Six drone models, three scenarios | Cloudy, sunny, evening | txt, xml, csv |

| Multi-Modal: Other | ||||||

| “CW coherent detection lidar for micro-Doppler sensing and raster-scan imaging of drones” Dataset | ||||||

| Rodrigo (2023) | Lidar Data | - | - | Micro-Doppler signatures, raster-scan images | Up to 500 meters detection | - |

| Multi-view Drone Tracking Dataset | ||||||

| Albl (2023) | Videos | - | - | Multiple cameras, 3D trajectory | Various difficulties | - |

| “Real-Time Drone Detection and Tracking With Visible, Thermal, and Acoustic Sensors” Dataset | ||||||

| Svanström (2020) | Videos, Audio Clips | 650 videos, 90 audio clips | Infrared: 320x256, Visible: 640x512 | Drones, birds, airplanes, helicopters | Various weather conditions | - |

References

Ajakwe, S. O., Ihekoronye, V. U., Mohtasin, G., Akter, R., Aouto, A., Kim, D. S., & Lee, J. M. (2022). VisioDECT Dataset: An aerial dataset for scenario-based multi-drone detection and identification (Dataset, v1). Mendeley Data. https://dx.doi.org/10.21227/n27q-7e06

Aksoy, M. C., Orak, A. S., Özkan, H. M., & Selimoğlu, B. (2019). Drone dataset: Amateur Unmanned Air Vehicle Detection (Dataset, v4). Mendeley Data. https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/zcsj2g2m4c/4

Al-Emadi, S. A., Al-Ali, A. K., Al-Ali, A., & Mohamed, A. (2019). Audio-based drone detection and identification using deep learning. In IWCMC 2019 Vehicular Symposium (IWCMC-VehicularCom 2019) (pp. 1-6).

Al-Sa’d, M., Allahham, M. S., Mohamed, A., Al-Ali, A., Khattab, T., & Erbad, A. (2019). DroneRF Dataset: A dataset of drones for RF-based detection, classification and identification (Dataset, v1). Mendeley Data. https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/f4c2b4n755/1

Albl, C., Li, J., Murray, J., Liao, C.-C., Ismalii, D., Awadaljeed, M., & Pan, Y. (2023). Multi-view Drone Tracking Datasets (GitHub repository). https://github.com/CenekAlbl/drone-tracking-datasets

Bennour, A., Bouridane, A., & Chaari, L. (2023). A real-time deep UAV detection framework based on a YOLOv8 perception module. In Intelligent Systems and Pattern Recognition (Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, 1941, pp. xxx-xxx). Springer.

Borji, A., & Itti, L. (2013). State-of-the-art in visual attention modeling. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 35(1), 185-207.

Carrió, A., Vemprala, S., Ripoll, A., Saripalli, S., & Campoy, P. (2018). Drone detection using depth maps. In 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS) (pp. 1034-1037). https://doi.org/10.1109/IROS.2018.8593405

Coluccia, G., Ghenescu, M., Piatrik, T., De Cubber, G., Schumann, A., … Blumenstein, M. (2017). Drone-vs-bird detection challenge at IEEE AVSS 2017. In 14th IEEE International Conference on Advanced Video and Signal Based Surveillance (AVSS) (pp. 1-6). https://doi.org/10.1109/AVSS.2017.8078464

DeDrone. (2024). Drone incidents database. https://www.dedrone.com/resources/incidents-new/all

Ding, S., Guo, X., Peng, T., Huang, X., & Hong, X. (2023). Drone detection and tracking system based on fused acoustical and optical approaches. Advanced Intelligent Systems, 5(10), e2300111. https://doi.org/10.1002/aisy.202300111

Xu, Z.-X. (2022). UAV Traffic Dataset for Learning-Based UAV Detection (Dataset). https://dx.doi.org/10.21227/enfv-kx52

Ezuma, M., Erden, F., Anjinappa, C. K., Ozdemir, O., & Guvenc, I. (2020). Drone Remote Controller RF Signal Dataset (Dataset). https://dx.doi.org/10.21227/ss99-8d56

Han, J., Ren, Y.-F., Brighente, A., & Conti, M. (2024). RANGO: A novel deep-learning approach to detect drones disguising from video-surveillance systems. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology. https://doi.org/10.1145/3641282

Harel, J., Koch, C., & Perona, P. (2007). Graph-based visual saliency. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 19 (pp. 545-552).

Hérault, J. (2010). Vision: Images, Signals and Neural Networks. World Scientific.

Hou, X., & Zhang, L. (2007). Saliency detection: A spectral residual approach. In 2007 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (pp. 1-8). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2007.383267

Itti, L., Koch, C., & Niebur, E. (1998). A model of saliency-based visual attention for rapid scene analysis. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 20(11), 1254-1259.

James, J. V., Cazzolato, B. S., & Grainger, S. (2019). An Insect-Inspired Detection Algorithm for Aerial Drone Detection Dataset (Dataset). https://adelaide.figshare.com/articles/software/ACRA_files_2018_and_2019_zip/21914208/1

Kim, J. H., Kim, N., & Won, C. S. (2023). High-speed drone detection based on YOLO-v8. In ICASSP 2023 – IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (pp. 1-2). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP49357.2023.10095516

Li, J., Ye, D. H., Kolsch, M., Wachs, J. P., & Bouman, C. A. (2022). Fast and robust UAV-to-UAV detection and tracking from video. IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computing, 10(3), 1519-1531. https://doi.org/10.1109/TETC.2021.3104555

Makrigiorgis, R., Souli, N., & Kolios, P. (2022). Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Dataset (Dataset). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7477569

McIntosh, L., & Maheswaranathan, N. (2015). A deep-learning model of the retina. Technical Report, Stanford Vision & Learning Lab.

Medaiyese, O., Ezuma, M., Lauf, A., & Adeniran, A. (2022). CardRF: An outdoor UAV/UAS/Drone RF signals dataset (Bluetooth & Wi-Fi) (Dataset). https://dx.doi.org/10.21227/1xp7-ge95

Melville-Smith, A., Finn, A., Uzair, M., & Brinkworth, R. (2022). Exploration of motion inhibition for the suppression of false positives in biologically inspired small-target detection algorithms from a moving platform. Biological Cybernetics, 116(5-6), 661-685.

Nayak, A., et al. (2022). Evaluation of fully convolutional one-stage object detection for drone detection. In ICIAP 2022 Workshops (Lecture Notes in Computer Science 13374, pp. 512-525). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-13324-4_37

O’Carroll, D. C. (1993). Feature-detecting neurons in dragonflies. Nature, 362, 541-543.

OpenCV. (2000). The OpenCV Library. Dr. Dobb’s Journal of Software Tools. https://opencv.org

Redmon, J., Divvala, S., Girshick, R., & Farhadi, A. (2016). You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (pp. 779-788).

Reis, D., Kupec, J., Hong, J., & Daoudi, A. (2023). Real-time flying-object detection with YOLOv8. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.12345.

Rodrigo, P. J., Larsen, H. E., & Pedersen, C. (2023). CW coherent-detection lidar for micro-Doppler sensing and raster-scan imaging of drones. Optics Express, 31, 7398-7412. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.483561

Sazdić-Jotić, B., Pokrajac, I., Bajčetić, J., Bondžulić, B., Joksimović, V., Šević, T., & Obradović, D. (2021). VTI_DroneSET_FFT (Dataset). https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/s6tgnnp5n2/3

Šević, T., Joksimović, V., Pokrajac, I., Radiana, B., Sazdić-Jotić, B., & Obradović, D. (2020). Interception and detection of drones using an RF-based dataset of drones. Scientific Technical Review (Online), 70(2), 29-34.

Shoemaker, P. A., O’Carroll, D. C., & Straw, A. D. (2005). Velocity constancy and models for wide-field visual-motion detection in insects. Biological Cybernetics, 93, 275-287.

Srinivasan, M. V., Laughlin, S. B., & Dubs, A. (1982). Predictive coding: A fresh view of inhibition in the retina. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 216, 427-459.

Srivastav, A., Shandilya, S. K., Datta, A., Yemets, K., & Nagar, A. (2023). Segmented Dataset Based on YOLOv7 for Drone vs. Bird Identification (Dataset). https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/6ghdz52pd7/5

Svanström, F. (2020). Real-Time Drone Detection and Tracking with Visible, Thermal and Acoustic Sensors (Dataset). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5500576

Tian, Z., Shen, C., Chen, H., & He, T. (2022). FCOS: A simple and strong anchor-free object detector. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 44(4), 1922-1933.

Ultralytics. (2024). YOLOv8 1.0 (GitHub repository). https://github.com/ultralytics/yolov8

Uzair, M., Brinkworth, R., & Finn, A. (2019). Insect-inspired small-moving-target enhancement in infrared videos. In 2019 IEEE International Conference on Digital Image Computing: Techniques and Applications (DICTA) (pp. 1-8).

Uzair, M., Brinkworth, R., & Finn, A. (2021). Detecting small-size and minimal-thermal-signature targets in infrared imagery using biologically-inspired vision. Sensors, 21(5), 1812. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21051812

Wang, H., Peng, J., & Yue, S. (2016). Bio-inspired small-target motion detector with a new lateral-inhibition mechanism. In 2016 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN) (pp. 4751-4758).

Wang, Y., Chen, Y., Choi, J., & Kuo, C.-C. J. (2019). Towards visible and thermal drone monitoring with convolutional neural networks. APSIPA Transactions on Signal and Information Processing, 8, e13.

Wiederman, S., Shoemaker, P., & O’Carroll, D. (2007). Biologically-inspired small-target detection mechanisms. In 2007 3rd Int. Conf. on Intelligent Sensors, Sensor Networks and Information (pp. 269-273).

Wiederman, S. D., Shoemaker, P. A., & O’Carroll, D. C. (2008). A model for the detection of moving targets in visual clutter inspired by insect physiology. PLoS ONE, 3(7), e2784.

Wiederman, S., James, J., Cazzolato, B., Grainger, S., & O’Carroll, D. (2022). An insect-inspired detection algorithm for aerial drone detection. Conference contribution (University of Adelaide). https://doi.org/10.25909/62906e8a09afd

Wisniewski, M., Rana, Z. A., & Petrunin, I. (2021). Drone-model identification by convolutional neural network from video stream. In 2021 IEEE/AIAA 40th Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC) (pp. 1-8). https://doi.org/10.1109/DASC52595.2021.9594392

Yang, X., et al. (2023). Video tiny-object detection guided by spatial-temporal motion information. In 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW) (pp. 3054-3063). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPRW59228.2023.00307

Zhao, Y., Ju, Z., Sun, T., Dong, F., Li, J., Yang, R., … Shan, P. (2023). TGC-YOLOv5: An enhanced YOLOv5 drone-detection model based on transformer, GAM & CA attention mechanism. Drones, 7(7), 446. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones7070446

Zhao, J., Li, J., Jin, L., Chu, J., Zhang, Z., … Liu, Y. (2023). The 3rd Anti-UAV Workshop & Challenge: Methods and results. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.07290

𑇄